As Hungate’s Unwrapping Archaeology events allow our volunteers and the public to sort through printing blocks dating back to the 19th century, it’s fitting to look into Norwich’s printing history. As I’ve been volunteering with Hungate as a part of my Museum Studies MA, I’ve found the Unwrapping Archaeology events to be a compelling look into the analogue, physical process which was necessary for the dissemination of information for centuries—and up until surprising recently!

Inspired by Hungate’s work, here is a short history of the first few decades of printing in Norwich—a story with more drama and intrigue than you might expect!

From the latter half of the 16th century through the end of the 17th, printing outside of London was limited both by law and demand. The 1662 ‘Act for preventing the frequent abuses in printing’ restricted printing presses in provincial cities, and even when the law lapsed, there was simply not enough readership to warrant the establishment of a press. However, this began to change as literacy increased and the public grew more interested in following printed news after the civil war. Newspapers were the primary way a press could sustain itself during this period, which brings us to the colourful history of early Norwich newspapers.

In 1701, a man named Francis Burges set up a humble press in Norwich with no competition. He published the first ever weekly newspaper for a provincial city in England: The Norwich Post, an impressive milestone in English history and in the history of communicative technology. A plaque just up the road from Hungate, on the Norwich University of the Arts building on Redwell Street, commemorates his work.

This press and the paper were moderately successful, but Burges unexpectedly died in 1706 at only 30 years old. When he died, two new presses were established in Norwich by opportunistic entrepreneurs. Samuel Hasbart, along with his bright apprentice Henry Crossgrove, printed The Norwich Gazette from Magdalen Street, and Thomas Goddard printed The Norwich Postman from his press near the Guild Hall. What these men did not realise was that Burges’ wife, Elizabeth, still planned on running The Norwich Post. By the end of 1706, despite the only moderate demand and moderate literacy of Norwich, the city had three newspapers.

In January of 1707, Hasbart’s Gazette began to disparage The Norwich Postman in its pages, writing that it was “a counterfeit ignorant News-Paper.” Hasbart also printed an open letter to Elizabeth Burges requesting she let his paper absorb hers. She refused. Hasbart then told the public he would lower his prices and offer free advertising. Eventually, the competition led all three presses to create newspapers for Great Yarmouth. All of these endeavors failed.

In 1708, The Norwich Post saw another early death of its owner. Although Elizabeth Burges died, the paper continued to be run by a man named Freeman Collins from London.

The pressure increased on all three presses when the Stamp Act created a tax which forced the presses to double the price of their newspapers. This caused Goddard’s Postman to close, but—not out of the game yet— it was replaced by another newspaper in 1713 from the same printer and publisher, the spectacularly named The Transactions of the Universe or Weekly Mercury.

The tax also caused The Norwich Post to close, though this could also be attributed to ANOTHER death at this press—Freeman Collins, who passed away in 1712. Not out of the running yet, however, as it was taken over by his wife, Susanna Collins. She started printing The Norwich Courant, which was described later in the 19th century as a “wretchedly printed newspaper”. Eventually, she passed the paper onto a former apprentice, Benjamin Lyon.

The intrigue continued at The Norwich Gazette—Goddard’s apprentice, Henry Crossgrove, had slowly taken more and more control over the press. Crossgrove began to print libelous content to edge out over the competition. This led to two arrests between 1715 and 1718, one for high treason. When Goddard realized he had lost control of his own paper, he tried to renegotiate terms with Crossgrove. The two clashed, and their business relationship ended acrimoniously. Goddard opened a fourth newspaper with Tory interests in mind. However, this project failed after only a few months. Historian David Stoker speculates that though this paper only existed for a few months, it may have driven the Norwich Courant out of business.

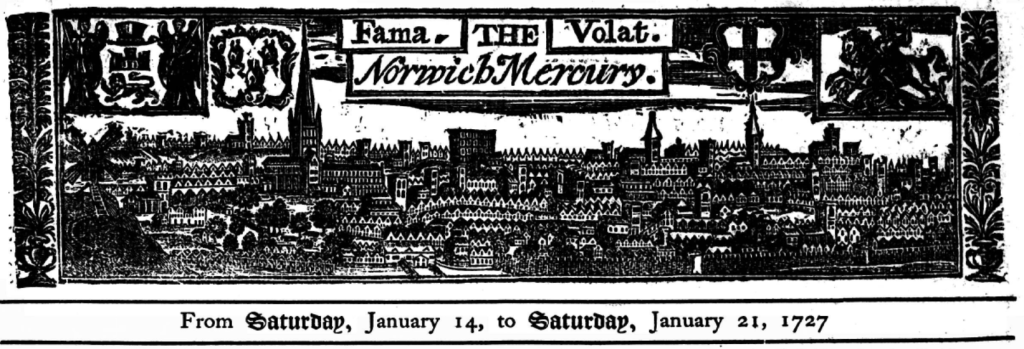

By 1720, only two newspapers remained: The Norwich Gazette, and The Transactions of the Universe or Weekly Mercury, by this time run by a man named William Chase. Eventually, as the field of competition became smaller, the reporting grew less scandalous, and both papers ran until 1744 when both Chase and Crossgrove died.

Much of this post has been summarised from David Stoker’s fascinating article “THE ESTABLISHMENT OF PRINTING IN NORWICH CAUSES AND EFFECTS 1660-1760”. I encourage anyone interested in this post to look into his work for more information.

Additionally, if local history, printing, or community volunteering is of interest to you, I encourage you to join us Saturdays and Sundays as we work through printing blocks dating back to the mid-19th century from the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society’s newspaper.

Written by Johanna Boyes

Image from the British Newspaper Archives